“the marginalisation of animals is today being followed by the marginalisation and disposal of the only class who, throughout history, has remained familiar with animals and maintained the wisdom which accompanies that familiarity: the middle and small peasant. the basis of this wisdom is the acceptance of the dualism at the very origin of the relation between man and animal. the rejection of this dualism is probably an important factor in opening the way to modern totalitarianism.”

-John Berger

FRACKING SHELL

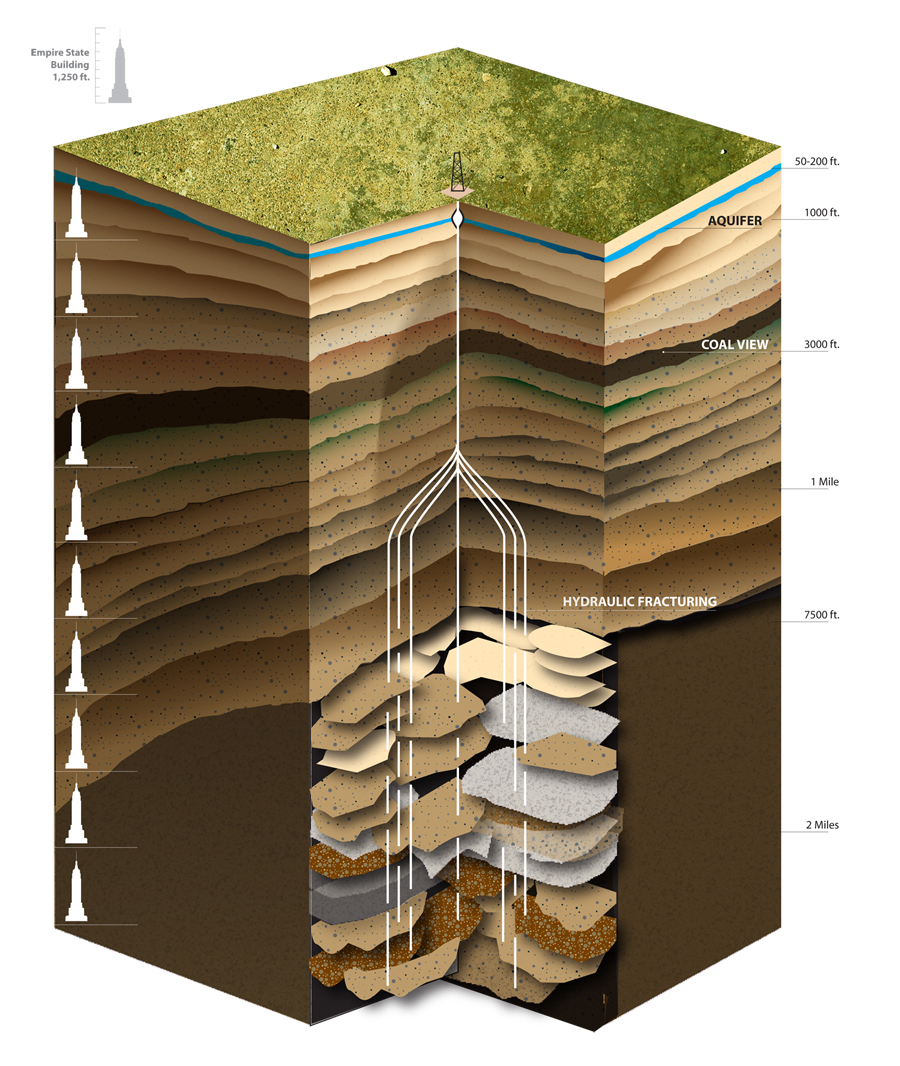

A really awesome flash animation explaining fracking

Gasland is a movie about the ways in which fracking has caused serious drinking-water hazards in several places in the USA. One of the pages on the website gives a really great description of what, exactly, fracking entails and how it's done. Click here to check out the animation.

An essay on the discourses of humanity and nature and the risks of hydraulic fracturing

The construction of “humanity” and “nature” as two entirely isolated entities is arguably the defining ideology of the modern world. Over the course of history and most dramatically since the advent of the industrial revolution, humankind has sought to establish a clearly defined boundary – both literally and metaphorically - between humans and nature. As a result of this continued effort to separate ourselves as a species from nature, the westernised 21st century world embodies a model of thinking that has all but forgotten the importance of our natural environment as the principal means to our survival. Technology has replaced nature as a means to advancing the human cause, and nature consequently becomes portrayed as a utility that can be manipulated in order to fulfil our needs regardless of its natural order and balance. In this essay I aim to investigate the issue of the use of hydraulic fracturing as a method of obtaining natural gas and oil and its effect on the environment using various discourses on nature, examples from the media as well as case-studies, in order to form a view of the way in which society deals with nature in the modern world and analyse the ways in which this view propagates or challenges the consumer and producer habits that have a negative effect on our environment.

Hydraulic fracturing is a relatively new method for extracting natural gas and oil in order to fulfil the demands of the automotive and energy industries. While the practice has been in existence since at least the late 1940s, (Montgomery 2010) it has seen a recent rise in popularity as a result of awareness of the non-sustainability of coal as a natural resource. (Hydraulic Fracturing and the Karoo 2011) The process of hydraulic fracturing involves “...drilling a hole deep into the dense shale rocks that contain natural gas, then pumping in at very high pressure vast quantities of water mixed with sand and chemicals. This opens up tiny fissures in the rock, through which the trapped gas can then escape.” (Harvey 2011) Because the process requires such a great amount of pressure to fracture the shale and release the desired products, each well can require up to 29 million litres of water to function properly, (Mounting Objections to Shell Fracking 2011) and there is a growing concern that groundwater at the drilling site may become contaminated by the chemicals used, as well as the possibility that potential methane leaks could cause fires. (Harvey 2011) The average expected lifespan for a drill-site is between 5 and 8 years, although productivity drops significantly after 5 years, (Say No to Fracking in the Karoo 2011) and once the wells have been pumped dry of resources, the contaminated water-solution may also leak back onto the surface and contaminate the earth as well as land water. (Harvey 2011) While oil companies insist that the dangers associated with hydraulic fracturing are negligible, (SAPA 2011) several water sources in Pennsylvania have been contaminated with fracking chemicals, (Rubinkam 2010) and environmental group Riverkeeper released information documenting over 100 cases of water contamination related to natural gas drilling in the United States alone. (Rubinkam 2010)

The most immediate concern in the process of hydraulic fracturing is the contamination of drinking water, although ground and air pollution are also factors. Although water is the earth's most abundant natural resource, reports claim that by 2025, two-thirds of the earth's population will not have access to safe drinking water. (Abbot 2004) The corporations behind many hydraulic fracturing expeditions in the United States were reluctant to release information regarding the chemicals used in the fracturing fluid in response to an outcry from the public after several sources of water became polluted as a result of drill sites in the area, (Rubinkam 2010) and only after the United States House of Representatives on Energy and Commerce undertook an investigation into the nature of substances used in the drillings, did it come to light that during the period between 2005 and 2009, 2.9 billion litres of chemicals were used in fracking sites across the country. (Waxman et al 2011) The most widely used of these chemicals was methanol which, according to the report, “is a hazardous air pollutant and is on the candidate list for potential regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act” (Waxman et al 2011) Additionally, 650 components of the fracturing liquid were made up of chemicals that are known carcinogens, or classified as hazardous to human and environmental health by the Clean Air and Safe Drinking Water acts. (Waxman et al 2011)

One major oil corporation that has come into the spotlight recently for their use of hydraulic fracturing is the Royal Dutch Shell company. (Hlongwane 2011) Shell is the market leader in the oil and gas industry and operates in more than 90 countries around the world, running more than 30 refineries and other chemical plants. (Shell at a Glance 2011) Several cases of environmental and human rights abuses have been reported regarding the corporation's presence in the Niger Delta. (Jolly 2011) The corporation was questioned by several parties in The Hague in January 2011: “Environmental organizations and business officials at the round-table meeting in The Hague differed sharply on how much responsibility Shell should take for the environmental damage. The devastation is particularly severe in the poor and fragile Niger Delta region, which has suffered more from oil production than perhaps any other place on earth after years of spills caused by rickety infrastructure, theft and sabotage.” (Jolly 2011) The corporation was accused of environmental degradation as well as human rights violations. (Smith 2010) Massive oil spills into the Niger Delta have been recorded, with estimated figures of total spills reaching up to 1,500,000 tonnes. (Alter 2010) Additionally, Shell has refused to pay for clean-up operations of the spills, since the company claims that 70% of the spills were the result of sabotage – and that they would not be prepared to pay for damages caused by sabotage for the fear of creating a “perverse incentive” to criminals. (Jolly 2011) Not only has Shell denied ultimate responsibility for the environmental damage, the corporation has also been accused of collaborating with the Nigerian government and forcing decisions upon the Nigerian people to suit the needs of the oil corporation rather than the population of the country. (Smith 2011) Shell has also been accused of violation of human rights in connection with the hangings of 9 anti-Shell protesters under Nigeria's government. (Stempel 2011)

Shell's latest controversial venture is their proposition to sink 24 wells in the Karoo over an area stretching from Sutherland to Somerset East. (Hlongwane 2011) The Karoo is an area relatively unaffected by human civilisation, as much of the area is farmland, conservation property or small local communities. (History of the Great Karoo 2011) The Karoo is also a water-sensitive area due to its arid climate, and the rich wildlife in the Karoo is dependent on a steady supply of water in order to survive. Shell has put a proposal forward to the South African government, and is currently awaiting approval for sinking the drilling holes in what the company terms an “exploration” of the area for suitable fracking sites. (Hlongwane 2011) Local communities are in active opposition to Shell using the Karoo as a fracking site, and there have been various accounts in the media of Shell insisting that the expedition would be of minimal environmental impact. (Hlongwane 2011) The objections to fracking in the Karoo are firstly the risk to the water supply of the area. The Karoo on average receives between 300 and 500mm of rainfall per year, (Department of Water Affairs 2005) and therefore could not possibly provide the amounts of water required to fuel 24 individual fracking sites. Shell has responded that they would opt to deliver water to the sites from less water-sensitive areas, which would require transporting truckloads of water to each site in very large trucks which would cause considerable damage to the roads of the area which are not suited to such heavy traffic. (Mounting Objections to Shell Fracking 2011)

The more serious concern with this process is the contamination of the local groundwater. If the groundwater in the area were to be contaminated it would have a severe impact on the human population of the region, but it would damage the ecosystems in the region even more dramatically. Sources of water in the Karoo are not abundant on the surface and therefore the land depends on the transfer of groundwater below the surface. (Department of Water Affairs 2005) Because the shale layer from which fracking releases natural gas is much lower than the sources of groundwater, the waste products carried through the pipes as well as the toxic substances left in the fractured rock may permeate the water supplies due to cracked pipes or extended fracturing. For this reason, a contamination in the water supply at any point in the greater Karoo area could pose a serious risk to the wildlife all the way across the region. This could have a devastating effect on the natural ecosystems in the area. Once again, Shell has assured any investigators that the incidents of water contamination in other countries cannot be considered definite consequences of hydraulic fracturing, and could also possibly be linked to a fault in the concrete lining of the fracking pipes and could be avoided easily. (Hlongwane 2011) Secondly, the presence of methanol or methane in the water supplies and in the air as a result of fracking could lead to serious fire risks, and the arid nature of the Karoo is vulnerable to fires and could therefore be gravely damaged as the result of fire. The fracking operations in the Karoo would also create the need for many more jobs in the area which would put increased pressure on the roads, generate noise pollution and disrupt the fragile ecosystems of flora and fauna in the region. Additionally, housing may be required for outsourced labourers. Naturally, employment would rise if Shell were to begin their operations in the area, but once the sources of natural gas and coal have been depleted, there would be a large population left in the area with no source of work.

The Karoo is also a place of great moral and spiritual significance to many South Africans – as an ancient land of the Khoisan people as well as a place of historical importance after European colonisation, since it has been the site of many conflicts during the Anglo-Boer war – and it is clear that a idealistic and romantic character has been built up around the area in folklore and due to its seclusion from civilisation. Before the colonisation of South Africa, the Khoisan lived a nomadic lifestyle and did not have any system of land ownership. (People of the Past 2010) The appropriation of land to individuals is a custom that was put in place during the time of the industrial revolution (Montagna 2006) and before this time, land that was not directly governed by towns was considered to belong to god, or indeed the church, which was the ruling monarchy of the time. (Montagna 2006) While the misappropriation of power during the rule of the Catholic church undeniably resulted in gross human rights violations, it is uncanny that the corporation, as the Christianity of the modern day, essentially has the same right as the church to claim any land it sees fit. However, in replacing a benevolent god of creation with an invisible and insatiable machine of production and consumption, the potential for abuse of the land is far greater. The division of land among individuals is also a dramatic turning-point in the way in which humankind views nature – the idea that individuals may “own” land or earn the right to own it by means of material wealth indicates a substantial disconnection between nature and humans. As a sacred or god-given expanse, the Earth was viewed as something that should be protected and nurtured in order for it to provide what humankind required for survival. Once land started to be considered as a commodity that could be used to generate money and power, the view of nature surely began to change from something that essentially ruled over man to something that man may rule over. The land is not divided according to its aesthetic or spiritual value, nor for its ecological function, but solely for its capital worth. Instead of man being punished by god with inherent sin that he must try to overcome, man is punished with inherent debt that must be repaid in order to survive in an artificial wilderness.

In the 21st-century world, the effect of human technologies such as the burning of fossil fuels, pollution of the environment and continued exploitation of vulnerable resources has left a legacy that threatens the earth's capacity to sustain life. Although hydraulic fracturing causes less carbon emissions and air-pollution than oil drilling or coal mining, (Montgomery 2010) the risks to air and water pollution pose substantial danger to the environment. (Harvey 2011) While it is arguable that an oil company has no place in an environmentally-conscious society by virtue of its nature, it is important to note that the typical cost of sinking one well is US$15 million. (Hlongwane 2011) If Shell is able to invest such large amounts of money in exploiting the environment, there is surely an obligation for it, as well as other large corporations to invest a substantial amount of their resources into developing environmentally sustainable practices instead of replacing outdated and unsafe methods of energy generation with equally damaging alternatives. According to John Hannigan in Environmental Sociology, the Ecosystem discourse that is still prevalent in today's environmental attitudes relies partially upon a “fusion of ecology and ethics” in the sense that ethical rights are extended to the environment and not solely to humans, supportive of the view that natural environments are a community rather than a commodity, (Hannigan 2007) and this is clearly not demonstrated by the disregard for the environmental impact that hydraulic fracturing may have on environments evident in the stances taken by Shell on the issue. (Hlongwane 2011)

Before the onset of the industrial revolution and the enlightenment philosophical movement, agriculture held an important position in society, not only because it was the only source of food production but also because it was an irreplaceable source of materials for the textile and clothing industry. (Montagna 2006) However, several advances in agricultural technology during this time resulted in an increased availability of foods and materials and caused living standards as well as population growth to increase exponentially in European countries, (Montagna 2006) which again forced the agricultural and textile industries to develop new technologies that were able to cater to a steadily increasing population of consumers. (Montagna 2006) As a result, machinery had to be developed in order to supply a larger number of people with an increased expectation of “necessities” for daily life. (Montagna 2006) The dominant enlightenment ideology of the time advocated reason and science as the primary vehicles for human “progress” and success, as well as the intellectual and societal freedom of the individual (Dickens 1992) and therefore the notion that humankind was responsible for the management of the earth and its resources became increasingly popular. This is still evident in the modern world – in a sense a combination of Herndl and Brown's typologies of regulatory discourse, in which nature is viewed as a resource and scientific discourse, in which nature is viewed as an object which may be exploited for the purposes of furthering the human understanding of earth and natural processes – as nature represents a body of knowledge that can be investigated and manipulated to achieve human progress. (Hannigan 2007) In his “An Answer To the Question: What Is Enlightenment”, Immanuel Kant summarises the view of humanity as opposed to nature: “The guardians who have so benevolently taken over the supervision of men have carefully seen to it that the far greatest part of them (including the entire fair sex) regard taking the step to maturity as very dangerous, not to mention difficult. Having first made their domestic livestock dumb, and having carefully made sure that these docile creatures will not take a single step without the go-cart to which they are harnessed, these guardians then show them the danger that threatens them, should they attempt to walk alone.” (Kant 1784) The analogy of livestock being “made dumb” is a powerful way to describe the extent to which humankind has manipulated the natural order of life to suit its own needs. Shell has demonstrated both in Nigeria and their attitudes regarding fracking in the Karoo that they place more value on profit than the health of the environment or of the communities in areas of potential business, and ultimately seek to control the planet and all its resources for the sake of commercial gain.

In The Corporation, it is explained that corporations are essentially considered “people” in the eyes of government, as corporations are granted the same rights as humans, such as the right to own property, loan and lend money. In this sense, the question of “man” versus nature becomes extremely distorted, and as a result the local communities both human and environmental become the metaphorical “nature” in the eyes of the corporation. Shell symbolises the industrial era ideals of using the earth's resources, regardless of scarcity or ecological importance, as a way to generate profit. Shell's initial resistance to releasing a list of the chemicals used in the hydraulic fracturing mixture indicate that they do not comply with the civil rights of the public stipulated by the environmental justice movement in Environmental Sociology - “the right to obtain information about one's situation; the right to a serious hearing when contamination claims are raised; the right to compensation from those who have polluted a particular neighbourhood; and the right to the democratic participation in deciding the future in the contained community.” (Hannigan 2007) So far, Shell has maintained a “gung-ho approach” (Hlongwane 2011) to the matter and plans to go ahead with the expedition, in the midst of an outcry from the community. It is also important to note that Shell has presence in the Nigerian government. Whether or not Shell has governmental ties in South Africa is unknown, but the fact that this company is morally dubious enough to manipulate governments into assisting their cause casts an almost psychopathic light on the Royal Dutch Shell Company at large.

A good example from the media of the extent to which the view of nature as a resource or a scientific experiment has penetrated the human consciousness is a television advertisement by General Electric aired in April 2008. (Leu 2008) The message of the advertisement is General Electric's commitment to recycling water and their constant innovation in water-saving techniques. The advertisement opens with an aerial view of a pastoral scene with clouds in the sky, and the camera slowly moves upwards and breaks through the clouds. Above the clouds, a team of men and women in white overalls are busy hauling buckets of water up from the earth and pouring them into various machines. Subsequent shots show the people working a large bellows which turns water into vapour and churning water through a press, as well as collecting falling water in test-tubes. The end of the video shows a long chain of people passing buckets of recycled water to one another and finally emptying them into a massive watering-can, which is tipped over when filled so that the water once again falls down to the earth below. There are several discourses evident in the advertisement, but the overall message is that every natural process has been explained with the use of humans or human technology – the ultimate anthropomorphism of nature. The voice-over in the advertisement states, “Just as nature re-uses water, GE water technologies turn billions of gallons into clean water each year.” (Leu 2008) which, in conjunction with the visuals, seems to be a claim that General Electric as a corporation on the forefront of human technology, understands nature's processes so thoroughly that it can reproduce them. There is a subtle reference to the idealistic, Arcadian view of nature throughout the advertisement in the sense that the natural processes of cloud formation and water recycling are envisioned as a process that involves conscious thought and practice. These processes would be explained by rational, Enlightenment-style discourse in terms of scientific research and evidence, yet the imagery in the advertisement creates a strong link with more mythological discourses. However, the result of this attitude towards the natural processes in conjunction with the presence of humans as the “workforce” behind the rainfall does not lend itself towards the idealistic portrayal of nature typical of the Romantic movement, (Dickens 2007) but rather plays on the fact that science seeks to supersede nature through imitating and eventually overcoming it.

The use of colour in the advertisement is also interesting as the characters in the clouds as well as their machinery and tools are all pure white. The effect of the colour selection is two-fold: the colour white is associated with innocence and purity, which idealises nature as sacred. This is communicated in a variety of ways, and generates interesting associations between the scientific and the mythological. While the characters are using man-made technology which explains the process of water recycling in a rational way, the presence of humans carrying out natural processes raises interesting pantheistic associations by illustrating nature as man and man as nature, as well as the obvious references made to modern theism through the portrayal of a “man in the clouds” which could be considered an analogy for a creator figure or indeed a much more paternal rendition of the “mother nature” figure. The use of the colour white also generates imagery of a scientific experiment or a laboratory setting, which is further communicated by the coat-like clothes worn by the people and by the use of test-tubes and the mechanical equipment which features throughout the advertisement. The selection of music is also a major part of the advertisement's effectiveness – the song that plays throughout the advertisement is “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” written by John Fogerty and performed by JuJu Stulbach. (Leu 2008) The lyrics of the song have an obvious literal connection to the theme of the advertisement; “I want to know, have you ever seen the rain come down on a sunny day?” (Have You Ever Seen The Rain? Lyrics 2010) In conjunction with the visuals, however, the lyrics lend themselves to the ideal of humankind being in control of the elements, or the fact that we have developed technologies that can imitate nature in any context – such as creating rain on a “sunny day”. The original recording of “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” was performed by Credence Clearwater Revival, and featured male vocals. The selection of a version of the song that features female vocals indicates the portrayal of nature as feminine, and further enhances the “mother nature” imagery being contrasted with the masculine character of rationalisation and science evident in the visuals of the advertisement. The end of the advertisement features a lightning-fast slide-show of icons including a green leaf, a turbine and a water droplet, eventually resolving into the spherical General Electric logo, and the pay-off line “imagination at work”.

The advertisement for General Electric is beautifully crafted and communicates its message in a very entertaining and endearing way, almost verging on the fairytale-like personalisation of nature. However, when one analyses it with specific regard to the depicted relationship between humankind and nature, there are several ways in which the advertisement propagates the errors in judgement that have caused countless fundamental problems regarding our view of nature in the greater enlightenment era. The portrayal of humans being in control of the earth's natural processes is a clear analogy for the lengths to which humankind has gone to imitate and “improve” nature. The earth has a natural ability to recycle water over the course of time, and in a system without industrial human interference, water sources would not be contaminated by waste-products and artificial chemicals. We have come to a point at which water recycling is a dire necessity because of the overpopulation of humankind on the planet and because of the use of toxic substances and irresponsible disposal of waste products, both organic and inorganic. Yet this campaign claims that General Electric – which, it should be noted, is a global energy, oil, gas and water conglomerate with a revenue in excess of US$750 billion in 2010 and presence in 160 countries (GE: Our Company 2011) – is dedicated to recycling water in order to sustain life on earth. General Electric is a corporation with a chequered environmental past, not only due to its participation in the gas and oil industries which endorse hydraulic fracturing among other dangerous technologies as environmentally sound procedures, but recently due to its pollution of the Hudson River in New York and its subsequent reluctance to take responsibility for the damage. (O’Donnell 2005) The company has been accused of “green-washing” in order to create a favourable identity for itself in an increasingly environmentally-conscious world, and when taking its nature and reputation into account, this becomes abundantly clear in the advertisement. Aside from creating a completely false set of values around General Electric, the advertisement takes an almost patronising stance on the reality of the environmental crisis. Anthropomorphism of nature has been evident in the earliest forms of recorded art, such as Khoisan rock-paintings (People from the Past 2010) and humankind has used symbolic expressions of nature as a human or animal form, or indeed a combination of the two, but in antiquity these depictions served as a way to make sense of the natural world and praise it. This typically post-modern conception of nature, however, is altogether different. Nature is portrayed as an ideal that humankind may aspire to, or a body of knowledge that man may eventually master and command. Instead of nature being portrayed as man so that it may communicate with us and show us how to understand the ways in which it works, man is portrayed as nature so that he may damage it in whichever way he sees fit, knowing that he has the power to undo this damage should he see the need.

Both General Electric and the Royal Dutch Shell Company share a common trait – the fact that neither corporation is willing to put a definite stop to the environmental damage caused directly and indirectly by their actions. Although on the surface both companies appear to be willing to make compromises and start working towards a sustainable industry, the positions they occupy as global powerhouses of the gas, oil and energy industries require them to take action against environmental damage which is proportional to the amount of harm they have caused. Simply offering the cheapest, most profitable alternative regardless of its potential effect on the environment is not a solution to the crisis we face; a profound change must be made in the way that nature is perceived in order to rectify the damage already caused to the planet as well as the inevitable damage that will be caused during an overlap from “dirty” to “clean” technology. My belief is that oil and gas companies do not have a place in the modern world. I believe that unless we make an abrupt and profound change in our relationship with the environment, we will face a real crisis in the near future that will not only affect human life, but the life of countless other species of animals on our planet. Whether these corporations use hydraulic fracturing, oil rigs or coal mines to generate the fossil fuels needed to keep the industry alive, the result will always be pollution of the air, water and ground; the disruption of plant and animal ecosystems; the depletion of naturally occurring substances and ultimately a huge risk to the well-being of the earth as we know it.

The world that has been constructed around us is one that is motivated by profit regardless of cost. Corporations such as Shell and General Electric as well as many others have come into such positions of power because of the fact that they have made more money than their competitors – by abusing the legal system, neglecting basic human rights and practising a blatant disregard for the health of the environment. These major corporations occupy positions in which they are able to make decisions which have global repercussions, yet they are motivated only by what will serve them best and not what needs to be done in order to preserve our natural world. Ultimately, corporations in this position cannot reflect the needs of the human world or the environment, since the corporation is neither a human nor natural entity that has been afforded human rights. In The Corporation, (Abbott 2004) the narrator draws a frightening parallel between the “personality” of corporations and the criteria for describing an individual as a psychopath. The reality of the 21st century world is that corporations with no social or ethical boundaries are dictating the course of our future, and without some type of ethical and environmental responsibility, we cannot hope to come to a solution that benefits both humankind and nature. I will conclude with the following extract from a speech by Lewis Pugh in response to Shell's proposed hydraulic fracturing operation: “I have visited the Arctic for 7 summers in a row. I have seen the tundra thawing. I have seen the retreating glaciers. And I have seen the melting sea ice. And I have seen the impact of global warming from the Himalayas all the way down to the low-lying Maldive Islands. Wherever I go, I see it. Now is the time for change. We cannot drill our way out of the energy crisis. The era of fossil fuels is over. We must invest in renewable energy. And we must not delay!”

Hydraulic fracturing is a relatively new method for extracting natural gas and oil in order to fulfil the demands of the automotive and energy industries. While the practice has been in existence since at least the late 1940s, (Montgomery 2010) it has seen a recent rise in popularity as a result of awareness of the non-sustainability of coal as a natural resource. (Hydraulic Fracturing and the Karoo 2011) The process of hydraulic fracturing involves “...drilling a hole deep into the dense shale rocks that contain natural gas, then pumping in at very high pressure vast quantities of water mixed with sand and chemicals. This opens up tiny fissures in the rock, through which the trapped gas can then escape.” (Harvey 2011) Because the process requires such a great amount of pressure to fracture the shale and release the desired products, each well can require up to 29 million litres of water to function properly, (Mounting Objections to Shell Fracking 2011) and there is a growing concern that groundwater at the drilling site may become contaminated by the chemicals used, as well as the possibility that potential methane leaks could cause fires. (Harvey 2011) The average expected lifespan for a drill-site is between 5 and 8 years, although productivity drops significantly after 5 years, (Say No to Fracking in the Karoo 2011) and once the wells have been pumped dry of resources, the contaminated water-solution may also leak back onto the surface and contaminate the earth as well as land water. (Harvey 2011) While oil companies insist that the dangers associated with hydraulic fracturing are negligible, (SAPA 2011) several water sources in Pennsylvania have been contaminated with fracking chemicals, (Rubinkam 2010) and environmental group Riverkeeper released information documenting over 100 cases of water contamination related to natural gas drilling in the United States alone. (Rubinkam 2010)

The most immediate concern in the process of hydraulic fracturing is the contamination of drinking water, although ground and air pollution are also factors. Although water is the earth's most abundant natural resource, reports claim that by 2025, two-thirds of the earth's population will not have access to safe drinking water. (Abbot 2004) The corporations behind many hydraulic fracturing expeditions in the United States were reluctant to release information regarding the chemicals used in the fracturing fluid in response to an outcry from the public after several sources of water became polluted as a result of drill sites in the area, (Rubinkam 2010) and only after the United States House of Representatives on Energy and Commerce undertook an investigation into the nature of substances used in the drillings, did it come to light that during the period between 2005 and 2009, 2.9 billion litres of chemicals were used in fracking sites across the country. (Waxman et al 2011) The most widely used of these chemicals was methanol which, according to the report, “is a hazardous air pollutant and is on the candidate list for potential regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act” (Waxman et al 2011) Additionally, 650 components of the fracturing liquid were made up of chemicals that are known carcinogens, or classified as hazardous to human and environmental health by the Clean Air and Safe Drinking Water acts. (Waxman et al 2011)

One major oil corporation that has come into the spotlight recently for their use of hydraulic fracturing is the Royal Dutch Shell company. (Hlongwane 2011) Shell is the market leader in the oil and gas industry and operates in more than 90 countries around the world, running more than 30 refineries and other chemical plants. (Shell at a Glance 2011) Several cases of environmental and human rights abuses have been reported regarding the corporation's presence in the Niger Delta. (Jolly 2011) The corporation was questioned by several parties in The Hague in January 2011: “Environmental organizations and business officials at the round-table meeting in The Hague differed sharply on how much responsibility Shell should take for the environmental damage. The devastation is particularly severe in the poor and fragile Niger Delta region, which has suffered more from oil production than perhaps any other place on earth after years of spills caused by rickety infrastructure, theft and sabotage.” (Jolly 2011) The corporation was accused of environmental degradation as well as human rights violations. (Smith 2010) Massive oil spills into the Niger Delta have been recorded, with estimated figures of total spills reaching up to 1,500,000 tonnes. (Alter 2010) Additionally, Shell has refused to pay for clean-up operations of the spills, since the company claims that 70% of the spills were the result of sabotage – and that they would not be prepared to pay for damages caused by sabotage for the fear of creating a “perverse incentive” to criminals. (Jolly 2011) Not only has Shell denied ultimate responsibility for the environmental damage, the corporation has also been accused of collaborating with the Nigerian government and forcing decisions upon the Nigerian people to suit the needs of the oil corporation rather than the population of the country. (Smith 2011) Shell has also been accused of violation of human rights in connection with the hangings of 9 anti-Shell protesters under Nigeria's government. (Stempel 2011)

Shell's latest controversial venture is their proposition to sink 24 wells in the Karoo over an area stretching from Sutherland to Somerset East. (Hlongwane 2011) The Karoo is an area relatively unaffected by human civilisation, as much of the area is farmland, conservation property or small local communities. (History of the Great Karoo 2011) The Karoo is also a water-sensitive area due to its arid climate, and the rich wildlife in the Karoo is dependent on a steady supply of water in order to survive. Shell has put a proposal forward to the South African government, and is currently awaiting approval for sinking the drilling holes in what the company terms an “exploration” of the area for suitable fracking sites. (Hlongwane 2011) Local communities are in active opposition to Shell using the Karoo as a fracking site, and there have been various accounts in the media of Shell insisting that the expedition would be of minimal environmental impact. (Hlongwane 2011) The objections to fracking in the Karoo are firstly the risk to the water supply of the area. The Karoo on average receives between 300 and 500mm of rainfall per year, (Department of Water Affairs 2005) and therefore could not possibly provide the amounts of water required to fuel 24 individual fracking sites. Shell has responded that they would opt to deliver water to the sites from less water-sensitive areas, which would require transporting truckloads of water to each site in very large trucks which would cause considerable damage to the roads of the area which are not suited to such heavy traffic. (Mounting Objections to Shell Fracking 2011)

The more serious concern with this process is the contamination of the local groundwater. If the groundwater in the area were to be contaminated it would have a severe impact on the human population of the region, but it would damage the ecosystems in the region even more dramatically. Sources of water in the Karoo are not abundant on the surface and therefore the land depends on the transfer of groundwater below the surface. (Department of Water Affairs 2005) Because the shale layer from which fracking releases natural gas is much lower than the sources of groundwater, the waste products carried through the pipes as well as the toxic substances left in the fractured rock may permeate the water supplies due to cracked pipes or extended fracturing. For this reason, a contamination in the water supply at any point in the greater Karoo area could pose a serious risk to the wildlife all the way across the region. This could have a devastating effect on the natural ecosystems in the area. Once again, Shell has assured any investigators that the incidents of water contamination in other countries cannot be considered definite consequences of hydraulic fracturing, and could also possibly be linked to a fault in the concrete lining of the fracking pipes and could be avoided easily. (Hlongwane 2011) Secondly, the presence of methanol or methane in the water supplies and in the air as a result of fracking could lead to serious fire risks, and the arid nature of the Karoo is vulnerable to fires and could therefore be gravely damaged as the result of fire. The fracking operations in the Karoo would also create the need for many more jobs in the area which would put increased pressure on the roads, generate noise pollution and disrupt the fragile ecosystems of flora and fauna in the region. Additionally, housing may be required for outsourced labourers. Naturally, employment would rise if Shell were to begin their operations in the area, but once the sources of natural gas and coal have been depleted, there would be a large population left in the area with no source of work.

The Karoo is also a place of great moral and spiritual significance to many South Africans – as an ancient land of the Khoisan people as well as a place of historical importance after European colonisation, since it has been the site of many conflicts during the Anglo-Boer war – and it is clear that a idealistic and romantic character has been built up around the area in folklore and due to its seclusion from civilisation. Before the colonisation of South Africa, the Khoisan lived a nomadic lifestyle and did not have any system of land ownership. (People of the Past 2010) The appropriation of land to individuals is a custom that was put in place during the time of the industrial revolution (Montagna 2006) and before this time, land that was not directly governed by towns was considered to belong to god, or indeed the church, which was the ruling monarchy of the time. (Montagna 2006) While the misappropriation of power during the rule of the Catholic church undeniably resulted in gross human rights violations, it is uncanny that the corporation, as the Christianity of the modern day, essentially has the same right as the church to claim any land it sees fit. However, in replacing a benevolent god of creation with an invisible and insatiable machine of production and consumption, the potential for abuse of the land is far greater. The division of land among individuals is also a dramatic turning-point in the way in which humankind views nature – the idea that individuals may “own” land or earn the right to own it by means of material wealth indicates a substantial disconnection between nature and humans. As a sacred or god-given expanse, the Earth was viewed as something that should be protected and nurtured in order for it to provide what humankind required for survival. Once land started to be considered as a commodity that could be used to generate money and power, the view of nature surely began to change from something that essentially ruled over man to something that man may rule over. The land is not divided according to its aesthetic or spiritual value, nor for its ecological function, but solely for its capital worth. Instead of man being punished by god with inherent sin that he must try to overcome, man is punished with inherent debt that must be repaid in order to survive in an artificial wilderness.

In the 21st-century world, the effect of human technologies such as the burning of fossil fuels, pollution of the environment and continued exploitation of vulnerable resources has left a legacy that threatens the earth's capacity to sustain life. Although hydraulic fracturing causes less carbon emissions and air-pollution than oil drilling or coal mining, (Montgomery 2010) the risks to air and water pollution pose substantial danger to the environment. (Harvey 2011) While it is arguable that an oil company has no place in an environmentally-conscious society by virtue of its nature, it is important to note that the typical cost of sinking one well is US$15 million. (Hlongwane 2011) If Shell is able to invest such large amounts of money in exploiting the environment, there is surely an obligation for it, as well as other large corporations to invest a substantial amount of their resources into developing environmentally sustainable practices instead of replacing outdated and unsafe methods of energy generation with equally damaging alternatives. According to John Hannigan in Environmental Sociology, the Ecosystem discourse that is still prevalent in today's environmental attitudes relies partially upon a “fusion of ecology and ethics” in the sense that ethical rights are extended to the environment and not solely to humans, supportive of the view that natural environments are a community rather than a commodity, (Hannigan 2007) and this is clearly not demonstrated by the disregard for the environmental impact that hydraulic fracturing may have on environments evident in the stances taken by Shell on the issue. (Hlongwane 2011)

Before the onset of the industrial revolution and the enlightenment philosophical movement, agriculture held an important position in society, not only because it was the only source of food production but also because it was an irreplaceable source of materials for the textile and clothing industry. (Montagna 2006) However, several advances in agricultural technology during this time resulted in an increased availability of foods and materials and caused living standards as well as population growth to increase exponentially in European countries, (Montagna 2006) which again forced the agricultural and textile industries to develop new technologies that were able to cater to a steadily increasing population of consumers. (Montagna 2006) As a result, machinery had to be developed in order to supply a larger number of people with an increased expectation of “necessities” for daily life. (Montagna 2006) The dominant enlightenment ideology of the time advocated reason and science as the primary vehicles for human “progress” and success, as well as the intellectual and societal freedom of the individual (Dickens 1992) and therefore the notion that humankind was responsible for the management of the earth and its resources became increasingly popular. This is still evident in the modern world – in a sense a combination of Herndl and Brown's typologies of regulatory discourse, in which nature is viewed as a resource and scientific discourse, in which nature is viewed as an object which may be exploited for the purposes of furthering the human understanding of earth and natural processes – as nature represents a body of knowledge that can be investigated and manipulated to achieve human progress. (Hannigan 2007) In his “An Answer To the Question: What Is Enlightenment”, Immanuel Kant summarises the view of humanity as opposed to nature: “The guardians who have so benevolently taken over the supervision of men have carefully seen to it that the far greatest part of them (including the entire fair sex) regard taking the step to maturity as very dangerous, not to mention difficult. Having first made their domestic livestock dumb, and having carefully made sure that these docile creatures will not take a single step without the go-cart to which they are harnessed, these guardians then show them the danger that threatens them, should they attempt to walk alone.” (Kant 1784) The analogy of livestock being “made dumb” is a powerful way to describe the extent to which humankind has manipulated the natural order of life to suit its own needs. Shell has demonstrated both in Nigeria and their attitudes regarding fracking in the Karoo that they place more value on profit than the health of the environment or of the communities in areas of potential business, and ultimately seek to control the planet and all its resources for the sake of commercial gain.

In The Corporation, it is explained that corporations are essentially considered “people” in the eyes of government, as corporations are granted the same rights as humans, such as the right to own property, loan and lend money. In this sense, the question of “man” versus nature becomes extremely distorted, and as a result the local communities both human and environmental become the metaphorical “nature” in the eyes of the corporation. Shell symbolises the industrial era ideals of using the earth's resources, regardless of scarcity or ecological importance, as a way to generate profit. Shell's initial resistance to releasing a list of the chemicals used in the hydraulic fracturing mixture indicate that they do not comply with the civil rights of the public stipulated by the environmental justice movement in Environmental Sociology - “the right to obtain information about one's situation; the right to a serious hearing when contamination claims are raised; the right to compensation from those who have polluted a particular neighbourhood; and the right to the democratic participation in deciding the future in the contained community.” (Hannigan 2007) So far, Shell has maintained a “gung-ho approach” (Hlongwane 2011) to the matter and plans to go ahead with the expedition, in the midst of an outcry from the community. It is also important to note that Shell has presence in the Nigerian government. Whether or not Shell has governmental ties in South Africa is unknown, but the fact that this company is morally dubious enough to manipulate governments into assisting their cause casts an almost psychopathic light on the Royal Dutch Shell Company at large.

A good example from the media of the extent to which the view of nature as a resource or a scientific experiment has penetrated the human consciousness is a television advertisement by General Electric aired in April 2008. (Leu 2008) The message of the advertisement is General Electric's commitment to recycling water and their constant innovation in water-saving techniques. The advertisement opens with an aerial view of a pastoral scene with clouds in the sky, and the camera slowly moves upwards and breaks through the clouds. Above the clouds, a team of men and women in white overalls are busy hauling buckets of water up from the earth and pouring them into various machines. Subsequent shots show the people working a large bellows which turns water into vapour and churning water through a press, as well as collecting falling water in test-tubes. The end of the video shows a long chain of people passing buckets of recycled water to one another and finally emptying them into a massive watering-can, which is tipped over when filled so that the water once again falls down to the earth below. There are several discourses evident in the advertisement, but the overall message is that every natural process has been explained with the use of humans or human technology – the ultimate anthropomorphism of nature. The voice-over in the advertisement states, “Just as nature re-uses water, GE water technologies turn billions of gallons into clean water each year.” (Leu 2008) which, in conjunction with the visuals, seems to be a claim that General Electric as a corporation on the forefront of human technology, understands nature's processes so thoroughly that it can reproduce them. There is a subtle reference to the idealistic, Arcadian view of nature throughout the advertisement in the sense that the natural processes of cloud formation and water recycling are envisioned as a process that involves conscious thought and practice. These processes would be explained by rational, Enlightenment-style discourse in terms of scientific research and evidence, yet the imagery in the advertisement creates a strong link with more mythological discourses. However, the result of this attitude towards the natural processes in conjunction with the presence of humans as the “workforce” behind the rainfall does not lend itself towards the idealistic portrayal of nature typical of the Romantic movement, (Dickens 2007) but rather plays on the fact that science seeks to supersede nature through imitating and eventually overcoming it.

The use of colour in the advertisement is also interesting as the characters in the clouds as well as their machinery and tools are all pure white. The effect of the colour selection is two-fold: the colour white is associated with innocence and purity, which idealises nature as sacred. This is communicated in a variety of ways, and generates interesting associations between the scientific and the mythological. While the characters are using man-made technology which explains the process of water recycling in a rational way, the presence of humans carrying out natural processes raises interesting pantheistic associations by illustrating nature as man and man as nature, as well as the obvious references made to modern theism through the portrayal of a “man in the clouds” which could be considered an analogy for a creator figure or indeed a much more paternal rendition of the “mother nature” figure. The use of the colour white also generates imagery of a scientific experiment or a laboratory setting, which is further communicated by the coat-like clothes worn by the people and by the use of test-tubes and the mechanical equipment which features throughout the advertisement. The selection of music is also a major part of the advertisement's effectiveness – the song that plays throughout the advertisement is “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” written by John Fogerty and performed by JuJu Stulbach. (Leu 2008) The lyrics of the song have an obvious literal connection to the theme of the advertisement; “I want to know, have you ever seen the rain come down on a sunny day?” (Have You Ever Seen The Rain? Lyrics 2010) In conjunction with the visuals, however, the lyrics lend themselves to the ideal of humankind being in control of the elements, or the fact that we have developed technologies that can imitate nature in any context – such as creating rain on a “sunny day”. The original recording of “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” was performed by Credence Clearwater Revival, and featured male vocals. The selection of a version of the song that features female vocals indicates the portrayal of nature as feminine, and further enhances the “mother nature” imagery being contrasted with the masculine character of rationalisation and science evident in the visuals of the advertisement. The end of the advertisement features a lightning-fast slide-show of icons including a green leaf, a turbine and a water droplet, eventually resolving into the spherical General Electric logo, and the pay-off line “imagination at work”.

The advertisement for General Electric is beautifully crafted and communicates its message in a very entertaining and endearing way, almost verging on the fairytale-like personalisation of nature. However, when one analyses it with specific regard to the depicted relationship between humankind and nature, there are several ways in which the advertisement propagates the errors in judgement that have caused countless fundamental problems regarding our view of nature in the greater enlightenment era. The portrayal of humans being in control of the earth's natural processes is a clear analogy for the lengths to which humankind has gone to imitate and “improve” nature. The earth has a natural ability to recycle water over the course of time, and in a system without industrial human interference, water sources would not be contaminated by waste-products and artificial chemicals. We have come to a point at which water recycling is a dire necessity because of the overpopulation of humankind on the planet and because of the use of toxic substances and irresponsible disposal of waste products, both organic and inorganic. Yet this campaign claims that General Electric – which, it should be noted, is a global energy, oil, gas and water conglomerate with a revenue in excess of US$750 billion in 2010 and presence in 160 countries (GE: Our Company 2011) – is dedicated to recycling water in order to sustain life on earth. General Electric is a corporation with a chequered environmental past, not only due to its participation in the gas and oil industries which endorse hydraulic fracturing among other dangerous technologies as environmentally sound procedures, but recently due to its pollution of the Hudson River in New York and its subsequent reluctance to take responsibility for the damage. (O’Donnell 2005) The company has been accused of “green-washing” in order to create a favourable identity for itself in an increasingly environmentally-conscious world, and when taking its nature and reputation into account, this becomes abundantly clear in the advertisement. Aside from creating a completely false set of values around General Electric, the advertisement takes an almost patronising stance on the reality of the environmental crisis. Anthropomorphism of nature has been evident in the earliest forms of recorded art, such as Khoisan rock-paintings (People from the Past 2010) and humankind has used symbolic expressions of nature as a human or animal form, or indeed a combination of the two, but in antiquity these depictions served as a way to make sense of the natural world and praise it. This typically post-modern conception of nature, however, is altogether different. Nature is portrayed as an ideal that humankind may aspire to, or a body of knowledge that man may eventually master and command. Instead of nature being portrayed as man so that it may communicate with us and show us how to understand the ways in which it works, man is portrayed as nature so that he may damage it in whichever way he sees fit, knowing that he has the power to undo this damage should he see the need.

Both General Electric and the Royal Dutch Shell Company share a common trait – the fact that neither corporation is willing to put a definite stop to the environmental damage caused directly and indirectly by their actions. Although on the surface both companies appear to be willing to make compromises and start working towards a sustainable industry, the positions they occupy as global powerhouses of the gas, oil and energy industries require them to take action against environmental damage which is proportional to the amount of harm they have caused. Simply offering the cheapest, most profitable alternative regardless of its potential effect on the environment is not a solution to the crisis we face; a profound change must be made in the way that nature is perceived in order to rectify the damage already caused to the planet as well as the inevitable damage that will be caused during an overlap from “dirty” to “clean” technology. My belief is that oil and gas companies do not have a place in the modern world. I believe that unless we make an abrupt and profound change in our relationship with the environment, we will face a real crisis in the near future that will not only affect human life, but the life of countless other species of animals on our planet. Whether these corporations use hydraulic fracturing, oil rigs or coal mines to generate the fossil fuels needed to keep the industry alive, the result will always be pollution of the air, water and ground; the disruption of plant and animal ecosystems; the depletion of naturally occurring substances and ultimately a huge risk to the well-being of the earth as we know it.

The world that has been constructed around us is one that is motivated by profit regardless of cost. Corporations such as Shell and General Electric as well as many others have come into such positions of power because of the fact that they have made more money than their competitors – by abusing the legal system, neglecting basic human rights and practising a blatant disregard for the health of the environment. These major corporations occupy positions in which they are able to make decisions which have global repercussions, yet they are motivated only by what will serve them best and not what needs to be done in order to preserve our natural world. Ultimately, corporations in this position cannot reflect the needs of the human world or the environment, since the corporation is neither a human nor natural entity that has been afforded human rights. In The Corporation, (Abbott 2004) the narrator draws a frightening parallel between the “personality” of corporations and the criteria for describing an individual as a psychopath. The reality of the 21st century world is that corporations with no social or ethical boundaries are dictating the course of our future, and without some type of ethical and environmental responsibility, we cannot hope to come to a solution that benefits both humankind and nature. I will conclude with the following extract from a speech by Lewis Pugh in response to Shell's proposed hydraulic fracturing operation: “I have visited the Arctic for 7 summers in a row. I have seen the tundra thawing. I have seen the retreating glaciers. And I have seen the melting sea ice. And I have seen the impact of global warming from the Himalayas all the way down to the low-lying Maldive Islands. Wherever I go, I see it. Now is the time for change. We cannot drill our way out of the energy crisis. The era of fossil fuels is over. We must invest in renewable energy. And we must not delay!”

APPENDIX

SPEECH BY LEWIS PUGH (SPOKESPERSON FOR TREASURE KAROO ACTION GROUP ) AT PUBLIC HEARINGS ON SHELL'S FRACKING PLANS FOR KAROO

Ladies and gentlemen, thank for the opportunity to address you. My name is Lewis Pugh. This evening, I want to take you back to the early 1990's in this country. You may remember them well. Nelson Mandela had been released. There was euphoria in the air. However, there was also widespread violence and deep fear. This country teetered on the brink of a civil war. But somehow, somehow, we averted it. It was a miracle! And it happened because we had incredible leaders. Leaders who sought calm.. Leaders who had vision. So in spite of all the violence, they sat down and negotiated a New Constitution. I will never forget holding the Constitution in my hands for the first time. I was a young law student at the University of Cape Town. This was the cement that brought peace to our land. This was the document, which held our country together. The rights contained herein, made us one. I remember thinking to myself - never again will the Rights of South Africans be trampled upon. Now every one of us - every man and every women - black, white, coloured, Indian, believer and non believer - has the right to vote. We all have the Right to Life. And our children have the right to a basic education. These rights are enshrined in our Constitution. These rights were the dreams of Oliver Tambo. These rights were the dreams of Nelson Mandela. These rights were the dreams of Mahatma Gandhi, of Desmond Tutu and of Molly Blackburn. These rights were our dreams. People fought and died so that we could enjoy these rights today. Also enshrined in our Constitution, is the Right to a Healthy Environment and the Right to Water. Our Constitution states that we have the Right to have our environment protected for the benefit of our generation and for the benefit of future generations. Fellow South Africans, let us not dishonour these rights. Let us not dishonour those men and women who fought and died for these rights. Let us not allow corporate greed to disrespect our Constitution and desecrate our

environment. Never, ever did I think that there would be a debate in this arid country about which was more important gas or water. We can survive without gas.... We cannot live without water. If we damage our limited water supply and fracking will do just that we will have conflict again here in South Africa. Look around the world. Wherever you damage the environment you have conflict. Fellow South Africans, we have had enough conflict in this land now is the time for peace. A few months ago I gave a speech with former President of Costa Rica. Afterwards I asked him "Mr President, how do you balance the demands of development against the need to protect the environment?" He looked at me and said : "It is not a balancing act. It is a simple business decision. If we cut down our forests in Costa Rica to satisfy a timber company, what will be left for our future?" But he pointed out : "It is also a moral decision. It would be morally wrong to chop down our forests and leave nothing for my children and my grandchildren." Ladies and gentlemen, that is what is at stake here today: Our children's future. And that of our children s children. There may be gas beneath our ground in the Karoo. But are we prepared to destroy our environment for 5 to 10 years worth of fossil fuel and further damage our climate? Yes, people will be employed but for a short while. And when the drilling is over, and Shell have packed their bags and disappeared, then what? Who will be there to clean up? And what jobs will our children be able to eke out? Now Shell will tell you that their intentions are honourable. That fracking in the Karoo will not damage our environment. That they will not contaminate our precious water. That they will bring jobs to South Africa. That gas is clean and green. And that they will help secure our energy supplies. When I hear this I have one burning question. Why should we trust them? Africa is to Shell what the Gulf of Mexico is to BP. Shell, you have a shocking record here in Africa. Just look at your operations in Nigeria. You have spilt more than 9 million barrels of crude oil into the Niger Delta. That's twice the amount of oil that BP spilt into the Gulf of Mexico. You were found guilty of bribing Nigerian officials and to make the case go away in America - you paid an admission of guilt fine of US$48 million. And to top it all, you stand accused of being complicit in the execution of Nigeria's leading environmental campaigner Ken Saro-Wira and 8 other activists. If you were innocent, why did you pay US$15.5 million to the widows and children to settle the case out of Court? Shell, the path you want us to take us down is not sustainable. I have visited the Arctic for 7 summers in a row. I have seen the tundra thawing. I have seen the retreating glaciers. And I have seen the melting sea ice. And I have seen the impact of global warming from the Himalayas all the way down to the low-lying Maldive Islands. Wherever I go I see it. Now is the time for change. We cannot drill our way out of the energy crisis. The era of fossil fuels is over. We must invest in renewable energy. And we must not delay! Shell, we look to the north of our continent and we see how people got tired of political tyranny. We have watched as despots, who have ruled ruthlessly year after year, have been toppled in a matter of weeks. We too are tired. Tired of corporate tyranny. Tired of your short term, unsustainable practices. We watched as Dr Ian Player, a game ranger from Natal, and his friends, took on Rio Tinto (one of the biggest mining companies in the world) and won. And we watched as young activists from across Europe, brought you down to your knees, when you tried to dump an enormous oil rig into the North Sea. Shell, we do not want our Karoo to become another Niger Delta. Do not underestimate us. Goliath can be brought down. We are proud of what we have achieved in this young democracy and we are not about to let your company come in and destroy it. So let this be a Call to Arms to everyone across South Africa, who is sitting in the shadow of Goliath: Stand up and demand these fundamental human rights promised to you by our Constitution. Use your voices - tweet, blog, petition, rally the weight of your neighbours and of people in power. Let us speak out from every hilltop. Let us not go quietly into this bleak future. Let me end off by saying this - You have lit a fire in our bellies, which no man or woman can extinguish. And if we need to, we will take this fight all the way from your petrol pumps to the very highest Court in this land. We will take this fight from the farms and towns of the Karoo to the streets of London and Amsterdam. And we will take this fight to every one of your shareholders. And I have no doubt, that in the end, good will triumph over evil.

Ladies and gentlemen, thank for the opportunity to address you. My name is Lewis Pugh. This evening, I want to take you back to the early 1990's in this country. You may remember them well. Nelson Mandela had been released. There was euphoria in the air. However, there was also widespread violence and deep fear. This country teetered on the brink of a civil war. But somehow, somehow, we averted it. It was a miracle! And it happened because we had incredible leaders. Leaders who sought calm.. Leaders who had vision. So in spite of all the violence, they sat down and negotiated a New Constitution. I will never forget holding the Constitution in my hands for the first time. I was a young law student at the University of Cape Town. This was the cement that brought peace to our land. This was the document, which held our country together. The rights contained herein, made us one. I remember thinking to myself - never again will the Rights of South Africans be trampled upon. Now every one of us - every man and every women - black, white, coloured, Indian, believer and non believer - has the right to vote. We all have the Right to Life. And our children have the right to a basic education. These rights are enshrined in our Constitution. These rights were the dreams of Oliver Tambo. These rights were the dreams of Nelson Mandela. These rights were the dreams of Mahatma Gandhi, of Desmond Tutu and of Molly Blackburn. These rights were our dreams. People fought and died so that we could enjoy these rights today. Also enshrined in our Constitution, is the Right to a Healthy Environment and the Right to Water. Our Constitution states that we have the Right to have our environment protected for the benefit of our generation and for the benefit of future generations. Fellow South Africans, let us not dishonour these rights. Let us not dishonour those men and women who fought and died for these rights. Let us not allow corporate greed to disrespect our Constitution and desecrate our

environment. Never, ever did I think that there would be a debate in this arid country about which was more important gas or water. We can survive without gas.... We cannot live without water. If we damage our limited water supply and fracking will do just that we will have conflict again here in South Africa. Look around the world. Wherever you damage the environment you have conflict. Fellow South Africans, we have had enough conflict in this land now is the time for peace. A few months ago I gave a speech with former President of Costa Rica. Afterwards I asked him "Mr President, how do you balance the demands of development against the need to protect the environment?" He looked at me and said : "It is not a balancing act. It is a simple business decision. If we cut down our forests in Costa Rica to satisfy a timber company, what will be left for our future?" But he pointed out : "It is also a moral decision. It would be morally wrong to chop down our forests and leave nothing for my children and my grandchildren." Ladies and gentlemen, that is what is at stake here today: Our children's future. And that of our children s children. There may be gas beneath our ground in the Karoo. But are we prepared to destroy our environment for 5 to 10 years worth of fossil fuel and further damage our climate? Yes, people will be employed but for a short while. And when the drilling is over, and Shell have packed their bags and disappeared, then what? Who will be there to clean up? And what jobs will our children be able to eke out? Now Shell will tell you that their intentions are honourable. That fracking in the Karoo will not damage our environment. That they will not contaminate our precious water. That they will bring jobs to South Africa. That gas is clean and green. And that they will help secure our energy supplies. When I hear this I have one burning question. Why should we trust them? Africa is to Shell what the Gulf of Mexico is to BP. Shell, you have a shocking record here in Africa. Just look at your operations in Nigeria. You have spilt more than 9 million barrels of crude oil into the Niger Delta. That's twice the amount of oil that BP spilt into the Gulf of Mexico. You were found guilty of bribing Nigerian officials and to make the case go away in America - you paid an admission of guilt fine of US$48 million. And to top it all, you stand accused of being complicit in the execution of Nigeria's leading environmental campaigner Ken Saro-Wira and 8 other activists. If you were innocent, why did you pay US$15.5 million to the widows and children to settle the case out of Court? Shell, the path you want us to take us down is not sustainable. I have visited the Arctic for 7 summers in a row. I have seen the tundra thawing. I have seen the retreating glaciers. And I have seen the melting sea ice. And I have seen the impact of global warming from the Himalayas all the way down to the low-lying Maldive Islands. Wherever I go I see it. Now is the time for change. We cannot drill our way out of the energy crisis. The era of fossil fuels is over. We must invest in renewable energy. And we must not delay! Shell, we look to the north of our continent and we see how people got tired of political tyranny. We have watched as despots, who have ruled ruthlessly year after year, have been toppled in a matter of weeks. We too are tired. Tired of corporate tyranny. Tired of your short term, unsustainable practices. We watched as Dr Ian Player, a game ranger from Natal, and his friends, took on Rio Tinto (one of the biggest mining companies in the world) and won. And we watched as young activists from across Europe, brought you down to your knees, when you tried to dump an enormous oil rig into the North Sea. Shell, we do not want our Karoo to become another Niger Delta. Do not underestimate us. Goliath can be brought down. We are proud of what we have achieved in this young democracy and we are not about to let your company come in and destroy it. So let this be a Call to Arms to everyone across South Africa, who is sitting in the shadow of Goliath: Stand up and demand these fundamental human rights promised to you by our Constitution. Use your voices - tweet, blog, petition, rally the weight of your neighbours and of people in power. Let us speak out from every hilltop. Let us not go quietly into this bleak future. Let me end off by saying this - You have lit a fire in our bellies, which no man or woman can extinguish. And if we need to, we will take this fight all the way from your petrol pumps to the very highest Court in this land. We will take this fight from the farms and towns of the Karoo to the streets of London and Amsterdam. And we will take this fight to every one of your shareholders. And I have no doubt, that in the end, good will triumph over evil.

REFERENCES

1. Jordan, B. (2011). 'Fracking' May Cloud Karoo Stars. Available: http://www.timeslive.co.za/sundaytimes/article895173.ece/Fracking-may-cloud-Karoo-stars. Last accessed 27 April 2011.

2. (2011). Mounting Objections to Shell Fracking. Available: http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/article1003536.ece/Mounting-objections-to-Shell-fracking. Last accessed 27 April 2011.

3. Nombembe, P and Johnson, G. (2011). Karoo Action Group Takes the Fight Forward. Available: http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/article1005221.ece/Karoo-Action-Group-takes-the-fight-forward. Last accessed 27 April 2011.

4. Hlongwane, S. (2011). Shell Takes gung-ho Stance on Karoo Fracking outrage. Available: http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/article941081.ece/Karoo-residents-concerned-about-gas-mining. Last accessed 27 April 2011.

5. Montagna, J. (2006). The Industrial Revolution. Available: http://www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1981/2/81.02.06.x.html. Last accessed 29 April 2011.

6. Harvey, F. (2011). Shale Gas Fracking – Q&A. Available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/apr/20/shale-gas-fracking-question-answer. Last accessed 30 April 2011.

7. Montgomery, C and Smith, M. (2010). Hydraulic Fracturing. Journal of Petroleum Technology. 62 (12), 26-41.

8. (2011). Hydraulic Fracturing and the Karoo. Available: http://www-static.shell.com/static/zaf/downloads/aboutshell/upstream/karoo_factsheet_hydraulic_fracturing.pdf. Last accessed 30 April 2011.

9. Rubinkam, M. (2010). Lawsuit: Gas drilling fluid ruined Pennsylavania water wells. Available: http://www.mnn.com/earth-matters/energy/stories/lawsuit-gas-drilling-fluid-ruined-pennsylavania-water-wells. Last accessed 30 April 2011.

10. Dickens, P. (1992). Introduction: Society, Nature and Enlightenment. In: Society and Nature. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. 1-21.

11. (2011). Say No To Fracking in the Karoo. Available: http://www.greenpeace.org/africa/en/News/news/Say-No-to-Fracking-in-the-Karoo/. Last accessed 30 April 2011.

12. Kant, I. (1784). An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?.Available: http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/documents/What_is_Enlightenment.pdf. Last accessed 30 April 2011.

13. Waxman, H; Markey, E; DeGette, D. (2011). Chemicals Used in Hydraulic Fracturing. Available: http://democrats.energycommerce.house.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Hydraulic%20Fracturing%20Report%204.18.11.pdf. Last accessed 1 May 2011.

14. (2011). Fracking Won't Harm Karoo. Available: http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/article947913.ece/Fracking-wont-harm-Karoo. Last accessed 1 May 2011.

15. Hannigan, J. (2007). Environmental Discourse. In: Environmental Sociology. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. 36-52.

16. (2011). Shell At A Glance. Available: http://www.shell.com/home/content/aboutshell/at_a_glance/. Last accessed 1 May 2011.

17. Jolly, D. (2011). Dutch Lawmakers Question Shell on Oil Pollution in Nigeria. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/27/science/earth/27nigeria.html?ref=earth. Last accessed 1 May 2011.

18. Smith, D. (2010). WikiLeaks cables: Shell's grip on Nigerian state revealed. Available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/dec/08/wikileaks-cables-shell-nigeria-spying. Last accessed 1 May 2011.

19. Alter, D. (2010). Gulf Spill Just A Drop In The Bucket Compared To What Happens Every Day, Everywhere Else. Available: http://www.treehugger.com/files/2010/06/gulf-spill-just-drop-in-bucket.php. Last accessed 1 May 2011.

20. Stempel, J. (2011). US Court Upholds Key Shell Ruling in Nigeria Case. Available: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/02/04/shell-nigeria-idUSN0424468420110204. Last accessed 2 May 2011

21. (2011). History of The Great Karoo. Available: http://www.thegreatkaroo.com/. Last accessed 2 May 2011.

22. Department of Water Affairs. (2005). A LEVEL I RIVER ECOREGIONAL CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR SOUTH AFRICA, LESOTHO AND SWAZILAND. Available: http://www.dwaf.gov.za/IWQS/gis_data/ecoregions/LEVEL_I_ECOREGIONSsigned_small2.pdf. Last accessed 28 April 2011.

23. Leu, J. (2008). Ads of the World | GE: Clouds. Online video. Available: http://adsoftheworld.com/media/tv/ge_clouds. Last Accessed 31 April 2011

24. (2010). Have You Ever Seen The Rain? Lyrics. Available: http://www.lyricsfreak.com/c/creedence+clearwater+revival/have+you+ever+seen+the+rain_20034350.html. Last accessed 29 April 2011.

25. Pugh, L. (2011). Speech by Lewis Pugh. Available: http://www.hwb.co.za/media-article.php?id=402. Last accessed 29 April 2011.

26. (2011). GE: Our Company. Available: http://www.ge.com/company/. Last accessed 28 April 2011.